Great Rift of Idaho, Megafloods Natural and Manmade and on Mars, Niagara of the West, Thousands of Springs

States: Idaho and Wyoming

Coordinates: 42 to 45 degrees North, 111 to 115 degrees West

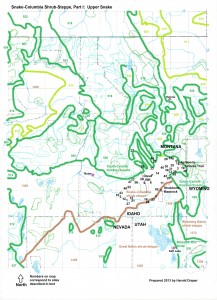

There are several distinct areas of this shrub-steppe ecoregion of the Columbia Plateau. For the purposes of this discussion, the ecoregion is subdivided into four sections, based on biological or geographic criteria. These are the Upper Snake River Plain, Treasure Valley and Owyhee Uplands, Oregon Lakes, and Columbia River Scablands.

The first area is the Upper Snake River Plain of southeastern Idaho and about a mile of Wyoming, which begins at the Magic Valley and extends east to the Wyoming border. Shoshone Falls within the Magic Valley is a biogeographic boundary, separating aquatic fauna upstream from downstream. The Magic Valley is an area of irrigated cropland which includes the lower Wood River, Thousand Springs Area, and Twin Falls upstream to Minidoka Dam. From American Falls upstream to St. Anthony is another agricultural area, the Upper Snake River Plain. The Teton Basin along the Teton River upstream from Rexburg is also an agricultural area. The area north of the Snake River is sagebrush and bunchgrass and is used for rangeland. Scattered lava flows and other volcanic features are present at Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve and Hells Half Acre. The three dry intermontane valleys drained by the upper Salmon River, Pahsimeroi River, Lemhi River, Birch Creek, Big Lost River, and Little Lost River are also sagebrush-covered and included in the ecoregion.

The entire Upper Snake River Plain contains lava flows created by the Yellowstone hotspot. The area was also shaped by megafloods. The notable Lake Bonneville dam failure and drainage about 15,000 years ago is believed to be responsible for some of the deep gorges along the Snake River. The spectacular Shoshone Falls (1), nicknamed as the Niagara of the West, is located in a city park in Twin Falls, which is part of the Magic Valley. Other tributary streams entering the Magic Valley also cut deep gorges. Downstream of Shoshone Falls the canyon walls are notable for seepage, creating the Thousand Springs area. Some canyons in the Thousand Springs area, such as Earl M. Hardy Box Canyon Preserve in Thousand Springs State Park (2), N42˚42’ W114˚49’ and adjacent Blind Canyon, have no drainage network upstream, and seepage emanates from the headwall. This type of feature has long been interpreted by geologists as resulting from seepage over thousands of years. At Box Canyon, the 11th largest spring in the United States creates a stream that flows a couple of miles into the Snake River. Lamb et al. (2008) reported that the head of the canyon actually contains waterfall plunge pools, and that there was evidence of past overspill in a large waterfall. The scour is not visible upstream because loess has been deposited on top of it. The age of the scoured bedrock notch at the head of the canyon was estimated at 45,000 years Before Present. This flood took place before the Bonneville event. The water source was probably the Big Lost River drainage or the Big Wood River drainage. Both rivers had megafloods when glacial lakes burst during the Pleistocene. These canyons are similar in appearance to many Martian canyons, and these are thus believed to be useful analogs to how the Martian canyons formed (Lamb et al. 2008).

Humans accidentally produced a smaller-scale megaflood of their own in 1976, when the Teton Dam collapsed while the reservoir was filling. Teton Dam (3), N43˚55’ W111˚32’, was located upstream from Rexburg in on the Teton River. Construction on a dam which would create a 17-mile-long reservoir commenced in 1975. The collapse of the partly filled reservoir in June 1976 caused extensive flooding downstream and damaged the hydroelectric facilities at Idaho Falls. The collapse occurred when the reservoir was only 22 feet before reaching full pool and was 270 feet deep. In about six hours, 250,000 acre-feet of water drained from the reservoir. The death toll downstream was 14. The government eventually paid about $400 million in damages to downstream users, including $1.7 million to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game for natural resource damages (Randle et al. 2000).

Initial investigations into the Teton Dam collapse focused on concerns about earthquake faults in the dam vicinity, raised in memos by the US Geological Survey (Boffey 1976). However, the December 1976 official report of an independent group blamed the dam collapse on poor engineering design work. The panel found evidence that water from the reservoir traveled through fissures in the canyon wall and made its way to the dam where it created tunnels and weakened the structure. Although the Bureau of Reclamation grouted the fissures and had built 250 earlier earthfill dams with no failures, geological conditions at the site were unusual and probably warranted additional measures (Boffey 1977). The dam was never reconstructed.

There is one Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site in the Upper Snake River subsection, American Falls Reservoir/Springfield Bottoms, Bureau of Reclamation, Idaho (4); coordinates are N42˚51’ W112˚50’. At 56,000 acres, this is one of the largest irrigation reservoirs, storing 1.7 million acre-feet of water as part of the Minidoka Project. A visitor center is at the dam, and a fish hatchery with nature trail along the Snake River (Idaho Department of Fish and Game) is below the dam. The reservoir is an Important Bird Area (IBA) for the California gull and waterbirds. Fort Hall National Historic Landmark (described below) is at the upper end on the Snake River opposite McTucker Island. The Fort Hall (Springfield) Bottoms are a waterfowl feeding ground fed by up to 50 cool, clear springs. The Sterling Wildlife Management Area on the reservoir is 3,600 acres covering a seven-mile stretch of the northern shoreline. It contains 1,500 acres of wetlands and is itself an IBA for waterbirds and shorebirds.

There are three National Historic Landmarks in Upper Snake River Plain. Two of them, Fort Hall and the Camas Meadows Battles, commemorate frontier history. Fort Hall, American Falls Reservoir and Fort Hall Indian Reservation (Shoshone-Bannock Tribe), Idaho (5) , N43˚1’ W112˚38’, was a fur trade outpost dating to 1834. It became the most important trading post in the Snake River Valley, established by Americans in disputed territory. It was also associated with overland migration as a stop on the Oregon and California Trails. Although the exact site cannot be located, the general vicinity containing the site is a joint management responsibility of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The Camas Meadows Battle Sites, Idaho (6), N 44˚21’ W111˚53’ and N44˚24’ W111˚55’, consists of two sites, one on private and one on state land, both at Kilgore, Idaho. The battle sites were important in the flight of the Nez Perce away from the U.S. Army in 1877. At Camas Meadows Camp southeast of Kilgore on private land along Spring Creek, the Nez Perce conducted a pre-dawn raid on the military camp which resulted in capture of most of the army’s mules, forcing the army to halt and allowing escape to Yellowstone National Park and Montana. At Norwood’s Seige on state land northwest of Kilgore, soldiers built 23 rifle pits out of lava rocks and defended themselves against the Indians for several hours. Camas Meadows is one of 38 sites in Nez Perce National Historical Park.

The third site commemorates a nationally significant event in modern history. Experimental Breeder Reactor (EBR) –I Atomic Museum, Idaho National Laboratory (7), N43˚31’ W113˚0’, was the site where in 1951, a research facility produced the first usable amount of electricity from a nuclear reactor. In 1963, the reactor achieved a self-sustaining chain reaction using plutonium as fuel, thus demonstrating breeder technology. Following decommissioning of EBR-I, EBR-II, a successor reactor, ran from 1964 to 1994 and provided electricity to Idaho National Laboratory. An on-site museum also has exhibits on prototype aircraft nuclear reactors. The museum is located 18 miles southeast of Arco on US Route 20-26.

National Natural Landmarks (NNLs) in the Upper Snake River subsection highlight the volcanic geology left behind as the area moved over the Yellowstone hotspot. Big Southern Butte, BLM, Idaho (8), N43˚24’ W113˚2’, is four miles wide, making it the largest volcanic dome on earth. Its age is approximately 300,000 years old. This makes it the largest area of volcanic rocks of young age in the U.S. and qualified it for NNL status.

Great Rift System, Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, Idaho (9), is unique in North America. Cracks in the earth extend for 62 miles, all included within Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve. There are three major lava fields, Carey, Craters of the Moon, and Wapi. The northern end of surface features are in the Pioneer Mountains and the southern end is the Wapi lava flow north of Minodoka Lake. Part of the Great Rift is included in the Craters of the Moon Wilderness area. Craters of the Moon is an IBA for violet-green swallow, mountain bluebird, raptors, and greater sage grouse. The northern end of the Great Rift is approximately at N43˚31’ W113˚37’ on Lava Creek and the south end is approximately at N42˚53’ W113˚13’ in the Wapi Lava Field.

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho (10), N42˚49’ W114˚57’, is located on the west side of the Lower Salmon Falls Reservoir and is the world’s richest deposit of upper Pliocene (five million years ago) mammal fossils. Fossils of the first true horse (now Idaho’s state fossil), the Sabertooth cat, mastodon, bear, and camel are found here. The site also contains a portion of the Oregon Trail, and ruts can be viewed along the access road. The Bonneville Flood 15,000 years ago left enormous fields of rounded lava boulders in the Hagerman area and carved the high bluffs where the fossils are found. The site was discovered in 1928. The Visitor Center is on US Route 30 in Hagerman.

Hell’s Half Acre Lava Field, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Idaho (11), N43˚19’ W112˚15’, is an unweathered fully exposed pahoehoe lava flow complete with rope coils. The NNL portion and main vent is on US Route 20 at milepost 287 (Twentymile) west of Idaho Falls. The Blackfoot Rest Area on I-15 also has trails through the lava field at both the northbound and southbound rest areas.

Niagara Springs, Thousand Springs State Park, Idaho (12), N42˚40’ W114˚40’, is located eight miles south from I-84 at exit 157 on road S1950E. This large spring discharges into the Snake River. It is part of the Hagerman IBA for nesting herons, eagles, and waterfowl.

North Menan Butte, BLM, Idaho (13), N43˚47’ W111˚58’, is located at the confluence of Henry’s Fork and the Snake River. These are the world’s largest tuff cones. A trail leads to the top of the butte. The south butte is privately owned. This late Pleistocene feature formed when a dike intruded into a shallow aquifer.

There is one Department of Energy National Environmental Research Park in the Upper Snake River subsection. Idaho Environmental Research Park, Department of Energy, Idaho (14), N43˚41’ W112˚41’, consists of the Idaho National Laboratory, 256,000 acres which have closed to livestock for over 50 years. It is the largest undisturbed block of undisturbed sagebrush steppe in the western U.S. and is an IBA for burrowing owl, loggerhead shrike, and ferruginous hawk.

The National Landscape Conservation System in the Upper Snake River subsection consists of the Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, Idaho. This was previously described under the Great Rift System NNL.

The National Park System in the Upper Snake River subsection consists of four sites:

Minidoka National Historic Site, Idaho (15), N42˚41’ W114˚15’, is located on Hunt Road off of Idaho State Route 25, 15 miles east of Jerome. This was the site of a relocation center for Japanese citizens from Alaska, Oregon, and Washington between 1942 and 1945. The facility consisted of 600 buildings and received irrigation water from Milner Dam. After 1945, the area was divided into farms.

Nez Perce National Historic Site, Idaho-Montana-Oregon-Washington, commemorates the sites, stories, and artifacts of the Nez Perce Tribe. Camas Meadows Battle Sites, previously described under NHLs, is one of the sites in this park. Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, Idaho, was previously described under the Great Rift System NNL and the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho, was previously described under NNLs.

Federally owned and federally licensed recreation lakes in Upper Snake River subsection include reservoirs operated by the Bureau of Reclamation, municipal utilities, electric cooperatives, and private power companies. American Falls Reservoir, Bureau of Reclamation, Idaho, is 56,000 acres and is described under Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network.

Lake Walcott, Bureau of Reclamation, Idaho (16), N42˚40’ W113˚19’, was constructed in 1906. Minidoka Dam is on the National Register of Historic Places. Part of the Minidoka Project, the reservoir and surrounding lands make up the Minidoka National Wildlife Refuge. An area near the dam is managed as Lake Walcott State Park. The project includes 17,700 acres of scattered property downstream and on the north side of the Snake River.

Little Wood River Reservoir, Bureau of Reclamation, Idaho (17), N43˚26’ W114˚2’, provides irrigation and reservoir recreation 11 miles north of Carey, Idaho.

Fish Creek Reservoir, BLM, Idaho (17), N43˚26’ W113˚50’, is a reservoir recreation area in the Pioneer Mountains east of Carey off of US Route 20-26-93.

Ashton Reservoir, Rocky Mountain Power, Idaho (18), N44˚6’ W111˚30’, is located on the Henrys Fork River west of Ashton.

Felt Dam, Fall River Electric Cooperative, Idaho (19), N43˚54’ W117˚17’, is a federally licensed facility on the Teton River east of St. Anthony, Idaho. It would have been the upstream end of Teton Reservoir, which was never filled because the dam failed (see overview paragraphs).

Idaho Falls City Power Plants, Idaho (20), consists of three hydroelectric facilities on the Snake River upstream (Upper Development Dam), downtown (City Dam), and downstream from Idaho Falls (Lower Development Dam); coordinates are N43˚28’ W112˚4’, N43˚29’ W112˚3’, and N43˚33’ W112˚3’. Also operated by Idaho Falls is Gem State Dam and Reservoir (20), N43˚25’ W112˚6’, which is a federally licensed hydroelectric reservoir on the Snake River, straddling the Bonneville-Bingham County Line south of Idaho Falls, providing reservoir recreation opportunities.

Idaho Power Company operates four facilities. Milner Dam and Reservoir, Milner Dam, Inc. and Idaho Power, Idaho (21), N42˚31’ W114˚1’, is a federally licensed 12-mile-long irrigation and hydroelectric reservoir extends downstream from Burley, Idaho on the Snake River. Twin Falls Dam, Idaho Power, Idaho (1), N42˚35’ W114˚21’, is upstream of Shoshone Falls and east of the City of Twin Falls on the Snake River. Upper Salmon Falls Dam, Idaho Power, Idaho (10), N42˚46’ W114˚54’, is on US Route 30 south of Hagerman. Lower Salmon Falls Dam, Idaho Power, Idaho (10), N42˚50’ W114˚54’, is on US Route 30 north of Hagerman. The Reservoir is adjacent to Hagerman Fossil Beds.

Magic Reservoir, Magic Reservoir Hydroelectric, Inc., Idaho (22), N43˚15’ W114˚21’, on the Big Wood River on US Route 20 east of Fairfield, is an IBA for gulls, terns, long-billed curlew, trumpeter and tundra swans.

The National Trail System in the Upper Snake subsection consists of National Historic Trails (NHTs) and National Recreation Trails (NRTs):

Lewis and Clark NHT, Idaho-Oregon-Washington, briefly enters the Upper Snake subsection in the area of the Lemhi Valley, Idaho.

The California NHT, Idaho-Nevada-California, main trail route along the Snake river follows the boundary between the Great Basin and the Snake River plain and consists of the following sites:

- Fort Hall, Idaho, was one of the most important Oregon-California trail landmarks. See Fort Hall NHL.

- American Falls, Idaho, is now under American Falls Reservoir (see under Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network).

- Massacre Rocks State Park, Idaho (23), N42˚40’ W112˚59’, is where the trail went between rock formations that were only wide enough for one wagon. I-86 now passes through the trail route. Although no massacre took place at the site, immigrants feared massacres when the trail closed in and visibility was low.

- Register Rock, Massacre Rocks State Park, Idaho (23), N42˚39’ W113˚1’, is a site where immigrants wrote their names on this large boulder just west of Massacre Rocks.

- Coldwater Hill, Idaho (24), N42˚37’ W113˚7’, was a trail landmark, today located at a rest area on I-86, milepost 19.

- Raft River Crossing, Idaho (24), N42˚34’ W113˚14’, is near the Parting of the Ways, where the California Trail turned southwest and left the Snake River plain.

Nez Perce National Historic Trail, Idaho, consists of two sites in the Upper Snake River subsection. This trail commemorates the Nez Perce flight from the US Army in 1877. Birch Creek Campground (25), N44˚8’ W112˚54’, is where Nez Perce warriors encountered a defensive circle of freight wagons and settlers. The resulting battle resulted in five dead. Hole-in-the-Rock Station (26), N44˚15’ W112˚14’, located one mile west of I-15 Exit 172 at the Beaver Creek crossing, is the site of a stage station where the Nez Perce stopped to cut telegraph lines. Camas Meadows Battle Sites NHL (6) was the site of a decisive encounter that prolonged the flight of the Nez Perce and allowed escape into Montana.

Oregon National Historic Trail, Idaho-Oregon, includes previously described sites for the California Trail: Fort Hall, American Falls, Massacre Rocks, Register Rock, Coldwater Hill, and California Trail Junction/Raft River Crossing sites. After the Parting of the Ways, the Oregon Trail continued along the Snake River and passed the following areas:

- Milner Historic Recreation Area, BLM, Idaho (21), N42˚31’ W114˚0’, is located on Milner Reservoir and includes the Milner Ruts. Access is from US Route 30, 11 miles west of Burley. A hiking trail leads along the ruts.

- Caldron Linn, BLM, Idaho (21), N42˚30’ W114˚8’, is not a trail site per se, but it shows why it was not a good idea for the emigrants to float down the Snake River. The Snake River narrows to a passage 40 feet wide. Wilson Price Hunt, on behalf of the Pacific Fur Company, tried to descend the Snake River in 1811 but his canoes capsized here and his party continued on land.

- Rock Creek Station and Stricker Homesite State Historic Site, Idaho Historical Society, Idaho (27), N42˚28’ W114˚19’, is five miles south of Hansen and was noted as an oasis in the desert for Oregon Trail travelers. In 1865, a store was built. The Oregon Trail crossed Rock Creek near here rather than downstream after it drops into a canyon near Twin Falls.

- Kanaka Rapids Ranch, Idaho (2), N42˚-40 W114˚48’, was along the Oregon Trail. Today it is a subdivision near Buhl, Idaho.

- Shoshone Falls Park, City of Twin Falls, Idaho (1), N42˚ 36’ W114˚ 24’, was near the trail. The roar of the falls was audible although the site was not directly on the trail, and emigrants would walk toward the river for a scenic view of the falls. When not diminished by irrigation diversions, this Snake River waterfall five miles east of Twin Falls is the Niagara of the West, dropping 212 feet. The city maintains a trail system along the canyon. The falls serve as a fish barrier and separate the Upper Snake freshwater ecoregion from the Columbia Unglaciated freshwater ecoregion.

- Thousand Springs, Idaho Power, Idaho (2), N42˚45’ W114˚50’, are adjacent to the trail on the north bank of the Snake River. The area was noted for waterfalls cascading off the canyon walls. The springs are diverted for hydroelectric power generation and are normally not visible.

- Upper Salmon Falls, Idaho (10), N42˚46’ W114˚54’, is adjacent to the Oregon Trail and is now a hydroelectric power facility (see federal recreation lakes).

- Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho (1) has an Oregon Trail segment which can be hiked.

There are two NRTs in the Upper Snake subsection. Cress Creek NRT, BLM Upper Snake Field Office, Idaho (28), N43˚40’ W111˚43’, is a 1.1-mile trail beginning at the Snake River northeast of Ririe. It interprets a grass-sagebrush community along a perennial creek with watercress.

Devils Orchard NRT, Craters of the Moon National Monument, Idaho (29), N43˚27’ W113˚32’, is located on the seven-mile loop road and is a one-half mile trail traversing island-like fragments of rock in a sea of cinders. Fragments of the North Crater Cinder Cone broke off and rafted to this spot. The trail is noted for displays of dwarf monkeyflowers.

There is one federally designated Wilderness Area in the Upper Snake Subsection. Craters of the Moon National Wilderness Area, National Park Service, Idaho (29), N43˚24’ W113˚31’, includes about 43,000 acres of the Great Rift area, mostly to the south of the tour loop road. Geographic features include Big Cinder Butte, the Watchman, Split Butte, Fissure Butte, Vermillion Chasm, and Carey Kipuka.

There are three National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) System areas in the Upper Snake Subsection. Camas NWR, Idaho (30), N43˚57’ W112˚15’, is a 10,000-acre wetland refuge harboring flocks of tundra and trumpeter swan, along with ducks, geese, and sandhill crane. The refuge water distribution system is made up of canals, dikes, and water control structures to support wetland maintenance. Unfortunately, the wetlands are shrinking due to droughts and groundwater pumping. Center pivot irrigation, which efficiently pumps groundwater, now surrounds the refuge. The area of wetlands that the refuge is able to maintain has been reduced from 4,000 acres to 2,000 acres. The refuge is now pumping groundwater to try to save the wetland area (Morse 2013). The refuge is an IBA for sage-steppe and waterfowl species and is known is a fall staging area for sandhill cranes.

Hagerman National Fish Hatchery, Idaho (2), N42˚45’ W114˚51’, produces salmon to mitigate for fish and wildlife losses caused by the construction of four dams on the lower Snake River (Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental, Ice Harbor in Washington). The Hatchery also produces 130,000 rainbow trout to mitigate for Dworshak Dam in northern Idaho. It is part of the Hagerman IBA for nesting waterfowl and eagles.

Minidoka NWR, Idaho (16), N42˚41’ W113˚24’, is a 21,000-acre refuge which manages the majority of land and water on Lake Walcott, including 80 miles of shoreline and extending 25 miles upstream from the dam. The site is an IBA for waterfowl, grasshopper sparrow, American white pelican, Swainson’s hawk, curlew, and tundra swan.

Other federal sites in Upper Snake subsection are listed below:

Cartier Slough Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (31), N43˚49’ W111˚55’, is located on the west side of Henry’s Fork west of Rexburg off State Route 33. It was purchased as mitigation for the Ririe (see) and Teton Projects (see overview). It is an IBA for waterfowl.

Mackay Reservoir and Chilly Slough, Idaho (38), N43˚ 58’ W113˚42’, located in the Big Lost River valley between the Lost River Range and the Pioneer Mountains, is an IBA for shorebirds and waterfowl.

U.S. Sheep Experiment Station, Agricultural Research Service, Idaho-Montana is a facility where research focuses on sheep breeding and the sustainability of grazing land ecosystems of the shrub-steppe and Rocky Mountains. Other research focuses on sheep management, vegetation dynamics following fire, and sage grouse population trends. Tracts in the Snake-Columbia shrub-steppe include 28,000 acres north of Dubois, Idaho (32), N44˚17’ W112˚10’; 1,200 acres near Kilgore, Idaho (32), N44˚25’ W111˚48’; and on the Little Lost River Highway north of Howe (33), N43˚52’ W113˚0’.

Snake River Area of Critical Environmental Concern, BLM, Idaho (34), is a designation for the South Fork Snake River from Palisades Reservoir 66 miles downstream to Roberts (Route 48 and I-15), and the Henry’s Fork from St. Anthony to its confluence with the Snake River. The area is an IBA and is the largest breeding population of bald eagle in Idaho and is the last stronghold of the yellow-billed cuckoo in the area. The river is bordered by the largest cottonwood gallery forest in the West.

St. Anthony Sand Dunes Research Natural Area, BLM, Idaho (35), N43˚59’ W111˚52’, surrounds the largest dunes in the Snake-Columbia shrub-steppe region. They contain endemic plants and a rare tiger beetle.

Stinking Springs Multiple Use Area, BLM, Idaho (34), N43˚37’ W111˚37’, includes a trail leading up a canyon from the Snake River, just of US 26, 20 miles east of Idaho Falls.

State and local sites in the Upper Snake subsection are listed below:

Ashton to Tetonia Trail State Park, Idaho (locations 18 to 19), is a 30-mile-long hiking-biking rail-trail in the far eastern Snake River Plain near Wyoming. Access points are Ashton N44˚4’ W111˚26’, Route 32 at Lamont N43˚58’ W111˚13’, Route 32 at Felt N43˚52’ W111˚11’, and Tetonia N43˚49’W111˚10’.

Carey Lake Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (36), N43˚20’ W113˚56’, is just west of Craters of the Moon. There is a 400-acre lake, which attracts migrating waterfowl and shorebirds and is an IBA.

Hagerman Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (2), N42˚46’ W114˚53’, is south of the town of Hagerman along US Route 30. Marshes and lakes harbor 30,000 to 40,0000 ducks, gulls, and bald eagles, making it an IBA.

Land of the Yankee Fork State Park, Idaho, commemorates Idaho mining history and also contains an archaeological site. The Challis Bison Kill Site (37), N44˚28’ W114˚13’, and the park interpretive center are located at the junction of US Route 93 and State Route 75 south of Challis. The ghost towns of Custer, Bayhorse, Bonanza, and the Yankee Fork Gold Dredge are included in the park.

Market Lake Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (39), N43˚47’ W112˚9’, is located at Roberts on I-15, contains cattail and bulrush marshes, and is an IBA for ducks and geese, especially pintails.

Mud Lake Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (40), N43˚53’ W112˚24’, is west of Camas NWR and is an IBA for white-faced ibis, Franklin’s gull, geese, swans, and ducks. It is a water storage reservoir for an irrigation district.

Niagara Springs Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (12), N42˚40’ W114˚43’, located eight miles south of I-84 Exit 157 at Wendell, is frequented by ducks and geese that winter along the Snake River and is an IBA.

Lake Walcott State Park, Idaho, is located on the north shore of Lake Walcott (16). It is a reservoir recreation area.

Sand Creek Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (18 and 41), contains the Chester wetlands across Henry’s Fork from US Route 20 at Chester, N44˚1’ W111˚36’. Ponds at Sand Creek, N44˚13’ W111˚37’, are located 18 miles north of St. Anthony on Sand Creek Road. The area is noted for grouse leks. This high desert –mountain transitional site is an IBA for sharp-tailed grouse and waterfowl.

Shoshone Falls Park, City of Twin Falls, Idaho (1), is described under Oregon National Historic Trail.

Sterling Wildlife Management Area, Idaho (42), N43˚0’ W112˚47’, is on the west side of American Falls Reservoir and consists of 11 wetland units that are managed for trumpeter swan, avocet, dowitcher, and Bohemian waxwing. The area is an IBA.

Thousand Springs State Park, Idaho (locations 2 and 43), is a five-unit park which includes Niagara Springs NNL (see) and is part of the Hagerman IBA. The Billingsley Creek unit, N42˚50’ W114˚53’, is a former ranch in the Hagerman Valley. The Earl M. Hardy Box Canyon Springs unit, N42˚42’ W114˚49’, contains the 11th largest spring in North America, a waterfall, and 250-foot canyon walls. It is believed to have been formed by a megaflood. The Malad Gorge unit, N42˚52’ W114˚52’, includes the Malad River as it crashes down a waterfall into Devil’s Washbowl and flows through a gorge. Downstream the Malad River flow is diverted into a flume by Idaho Power for power generation. Upstream are Oregon Trail ruts in the Kelton Trail area, N42˚52’ W114˚51’. The Ritter Island area, N42˚44’ W114˚51’, includes a historic house along the river and three waterfalls; it is adjacent to the Thousand Springs area, which is owned by Idaho Power and diverted for hydroelectric power generation. The Vardis Fisher unit, N42˚49’ W114˚52’, east of Hagerman includes the University of Idaho Trout Research Center.

Private sites in the Upper Snake Subsection are listed below:

Birch Creek Fen, the Nature Conservancy, Idaho (44), N44˚14’ W112˚58’, is on the Lemhi-Clark County line off State Route 28. It is an area of unique low elevation peatlands along Birch Creek. The fen harbors rare plants (Moseley 1992).

Croft Archaeological Preserve, the Archaeological Conservancy, Idaho (45), is a private National Register of Historic Places site (Wasden Owl Cave site) located west of Idaho Falls. Bison were driven into a lava tube, trapped, and speared. The ten-acre site containing three lava tube caves was in use from about 10,000 to 8,000 years ago. Remains of mammoth, bison, pronghorn antelope, and camel are present (Wilkins 2013).

Idaho’s Mammoth Cave, Idaho (46), N43˚4’ W114˚25’, is a lava tube on State Route 75 eight miles north of Shoshone that offers commercial tours. Shoshone Indian Ice Cave, Idaho (46), N43˚10’, W114˚21’, is nearby on State Route 75, 16 miles north of Shoshone and is also a lava tube that offers commercial tours.

Silver Creek Preserve, the Nature Conservancy, Idaho (47), N 43˚19’ W114˚9’, is an IBA west of Picabo on US 20. The wetlands are noted for trumpeter swan, waterfowl, wading birds, and warblers. Silver Creek is noted for fly fishing.

Teton Basin, Idaho-Wyoming (48), N43˚43’ W111˚9’, is at the far eastern edge of the Snake River Plain. The Teton Regional Land Trust manages conservation easements that protect wetlands and fens. The area, which is centered on Driggs, Idaho, is an IBA for sandhill crane, trumpeter swan, and curlew.

Thousand Springs, Idaho Power, Idaho (2), N42˚45’ W 114˚50’, are diverted for hydroelectric power generation and are normally not visible.

Further Reading

Boffey, Philip M. 1976. Teton Dam Collapse: Was It a Predictable Disaster? Science 193:30-32.

Boffey, Philip M. 1977. Teton Dam Verdict: A Foul-Up by the Engineers. Science 195:270-272.

Lamb, Michael P., William E. Dietrich, Sarah M. Aciego, Donald J. DePaolo, and Michael Manga. 2008. Formation of Box Canyon, Idaho, by Megaflood: Implications for Seepage Erosion on Earth and Mars. Science 320:1067-1070.

Morse, Susan. 2013. In Idaho, a Wetlands Refuge “in Transition.” Refuge Update 10(1):6 (January/February).

Moseley, Robert K. 1992. Ecological and Floristic Inventory of Birch Creek Fen, Lemhi and Clark Counties, Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise. Cooperative Challenge Cost-Share Project of Targhee National Forest, Salmon District Bureau of Land Management, and Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Accessed June 15, 2013, at http://fishgame.idaho.gov/ifwis/idnhp/cdc_pdf/moser92i.pdf.

Randle, Timothy J., Jennifer A. Bountry, Ralph Klinger, and Allen Lockhart. 2000. Geomorphology and River Hydraulics of the Teton River Upstream of Teton Dam, Teton River, Idaho. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Denver. Accessed June 15, 2013, at http://www.usbr.gov/pmts/sediment/projects/TetonRiver/Reports/index.html.

Wilkins, Cory. 2013. An Ancient Preserve in Idaho. American Archaeology 17(1):46-47 (Spring 2013).